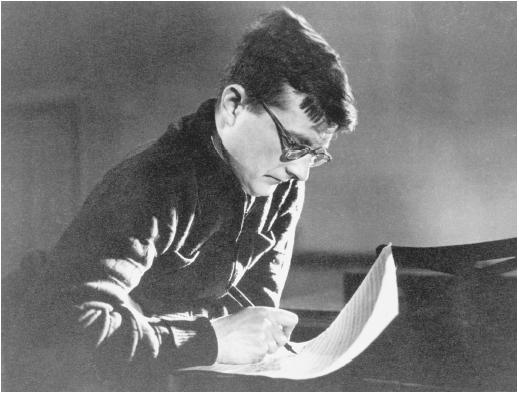

In an excellent monograph on Shostakovich's career in film ('Dmitri Shostakovich: A Life in Film' published by I.B.Tauris), John Riley states that "film critics often seem oblivious to the soundtrack". A statement that is without and shadow of a doubt very true. I have spent maybe ten or more times watching Klimov's 'Sport,Sport,Sport' in order to subtitle it (& produce annotated notes on the film) and although I knew that the film was made in collaboration with Schnittke it is only now that I am beginning to see how the soundtrack contributes to the film as a whole. I am no musicologist and am rather uncertain as to how one can write about this aspect of the film. Yet there seems no end to the amount of Soviet films in which the soundtrack is vital to an understanding of the film itself.

John Riley's book on Shostakovich's work has some fascinating accounts of his work on almost fourty films. Even though Shostakovich's contribution varied in terms of quality according to the period in which he worked and the people with whom he collaborated on a film, for many of these films the music contributes to an understanding of the very meaning of the film. Examples of great films he contributed to were many films by Kozintsev and Trauberg (New Babylon, Alone, The Youth of Maksim, Simple People and then with Kozintsev alone in Pirogov and then in the masterpieces Hamlet and King Lear) Yutkevich's The Golden Mountains and Man with a Gun as well as The Counterplan co-directed with Ermler), Gendelshtein's Love and Hate, and then various films with Arnshtam (including Girlfriends and Zoya), with Faintsimmer (The Gadfly) and with other great directors such as Kalatozov, Dovzhenko, Roshal and Joris Ivens. He also worked on the soundtrack of Chiaureli's films during the most dangerous period for Shostakovich after the denunciation of him at the 1948 Congress of Musicians, though obviously in this case it was a question of physical survival which led him rather reluctantly to this work.

Of course, great film music was also to be contributed by the likes of Prokofiev (in his work with Eisenstein and Faintsimmer's 'Lieutenant Kizhe') and the trio of Schnittke, Gubaildulina and Artemyev were to provide some of the greatest soundtracks in world cinema. Moreover, often music which was surpressed or discouragd as music could turn up in the films where its radical innovation would be less likely to be noted. Film was an area where composers not conforming to Socialist Realist musical canons were still able to work. And thankfully. Cinema in the Seventies, for example, would be immensely enriched by the contributions of Schnittke, Gubaidulina, Ganelin, Kupriavicius who were practically banished from other musical arenas just as film music was the shelter for Shostakovich decades previously.

Soviet cinema would develop new forms of sound-visual interaction. The 'song film', the symphonic type of dramaturgy, the musical comedy, Eisenstein and Prokofiev's experiments in sound-visual counterpoint, polystylism in the late thaw. Popular film would also have its Dunaevsky's and Kancheli's who would add to the extraordinary quantity and quality of popular tunes and songs.

I recognise my own woeful obliviousness in the past of the place of music in films but this neglect of the past will hopefully be rectified by much more attention in the future. Apart from Riley's superb account of Shostakovich's work in cinema, Tatiana Egorova's hostorical survey is a fine introduction to this subject in a historical perspective. However, the book is appallingly translated and edited (at least my 1997 edition of it is). A pity because the book seems the only general history in this field and has some fascinating accounts of many films from a musicological perspective.