In a recent post Tatiana Daniliyants I posted an interview with a Russian filmmaker who has filmed abroad (in her case, Italy). This post tries to look at the experience of a British documentary filmmaker, Jake Mobbs, who has made a journey in the opposite direction filming his documentary in Russia. The film premiered at the ArtDocFest (Russia's main festival of documentary film). It was singled out for strong praise by the Chairman of the Jury, Andrei Smirnov, during the closing ceremony (and also later in a print interview with the Russian New Times). A social documentary, initially shot to support a charity in the city of Perm, it has very high production values and, as well as in Moscow, premiered in London last month to a packed audience at the Riverside Studios. The subject matter of a group of street kids who organize their own society in spite of a hostile environment and deal with a truly toxic situation arisen in part due to the catastrophic social effects of post-Soviet transition is, of course, not a new subject and yet this type of socially-based documentary seems to have become - post-perestorika- ever more rare in Russia. The film is being released at a time when the figure of the child in Russia has become politicized due to the promulgation of a new law banning adoptions of Russian orphans to the US and the opposition voiced by part of civil society to this new law.

Could you tell me what the catalyst was for filming in another country and how you think it is (would have been) different from filming a social documentary in the UK?

I first got the idea to make a film in Russia when I went to Perm to visit my sister who was working with Love's Bridge, a charity working with under-privileged children. At the time I didn’t have any intention to make a feature-length film, but to produce a short promotional film to support the charity. Over the next few years, it grew into a much bigger project - a longer, cinematic film that could potentially be broadcasted and reach a bigger audience.

Although there are similar charities in the UK, most of them already have a wealth of media support and may not have invested the time and effort as Love's Bridge did in my idea to make a documentary. Throughout this project, it wasn't particularly easy to obtain support and advice from the charities in the UK. The living conditions in Perm and the freezing weather, gave our film a striking and unique angle that you would not find in a story set in the UK and as a result, we managed to secure necessary funds to start filming.

How was your film was received in Russia?

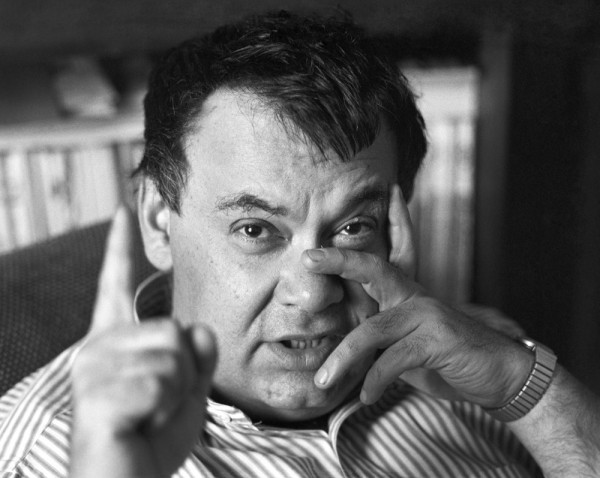

It was an honour to hold our first public screening in Moscow. Initially, I did not expect it to be accepted into the festival. Although the film isn’t political, it is difficult for many Russians to appreciate a film about an uncomplimentary side of Russia made by a foreigner. In the end, it went surprisingly well and Andrei Smirnov commended me for coming to Russia to create a wonderful and important film.

ArtDocFest is a fantastic festival and very liberal in its ideas. The organisers and audience were extremely welcoming towards me and my film. As to why I gave the film the title 'fairytale', it took a bit of explaining and discussion after the screening, but it was clear to them that I had given these teenagers a stage to tell their story and it was an important story to tell.

Did you have any models (films or filmmakers) when you thought about making this film in Russia? Have you been particularly struck by any films about Russia shot by foreign filmmakers or any films shot in the UK by Russian filmmakers?

There were two films that struck me as extremely powerful when I was researching this topic. One was about homeless children living on the subways in Moscow called Children of Leningradsky, made by a Ukrainian filmmaker. The other was a film about homeless people living in train tunnels in New York called Dark Days. I was compelled by both of these films and they inspired me, not just in their style but from the change in the way you view homelessness after watching it. I haven’t seen many films shot in the UK by Russian filmmakers, apart from a selection of short documentaries shot by Russian students, shown at the Russian film festival in London.

How was the actual process of film-making in Russia - what felt strange or unusual and what difficulties did you have in filming as a foreign film-maker? (Were there any advantages or disadvantages about your status as a foreign film-maker?)

I think Russia is a relatively straightforward place for filming, as long as you carry a stamped document explaining what you’re doing, in case you’re stopped by the police. In Perm, the police presence is minimal and if you don’t stand out too much, you can easily film without being noticed. We were caught out once when the teenagers in our film were raided and we were ordered to hand over our tapes. Fortunately, we were filming on flash cards and after some confused inspection, these were handed back to us. Most institutions were happy with us filming after we explained our project. On some occasions, permission was granted because the film was made for a foreign audience. The unique situation of a foreign filmmaker taking interest in their work made it more appealing for them to spend time helping us.

Why did you decide to film the subject that you did?

Is there anything especially interests you about any Russian documentary films that you have seen? What is your overall vision of documentary film-making? What trends and tendencies in documentary particularly interest you?

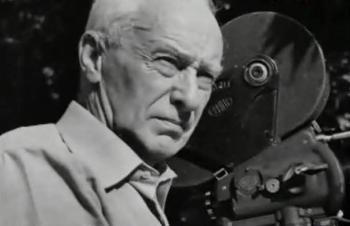

I find Russia a fascinating place, so any documentary made in the country interests me. I enjoyed Winter Go Away - which gave an important insight into the political protests from the view of the demonstrators. Contest, about a beauty pageant in a women’s prison in Novosibirsk was a great way of understanding life inside Russian prisons. I also enjoy the work of Marina Goldovskaya, especially A Bitter Taste of Freedom about Anna Politkovskaya. These are all very personal films about real Russian characters.

A Russian Fairytale Trailer from A Russian Fairytale on Vimeo.

I see documentary as a platform to educate and inspire change. For an hour or two, you can experience the lives of others, so far-flung that you may not have even known of their existences otherwise and sometimes it can take courage to step inside this world. It’s important to see some element of hope in a documentary - which gives people the inspiration to get up and make a difference, by donating or contributing to street action.

Films made about ordinary people who choose not to conform to society’s rules have a particular interest to me. There’s a growing trend to break rules, to make a mark and be noticed, whether politically or otherwise. Films that capture this spark and show our society in a new light are becoming increasingly important.

All born in the years after the collapse of the Soviet Union, they have created their own kind of society as together they battle with freezing temperatures, harassment from the police and their very vulnerable existence, using drink and drugs to block out the horrors of life and escape into fantasy.

The four face their brutal, unforgiving world with grit and often caustic humour, but now, on the brink of adulthood, time is running out for any of the group to escape their toxic situation.

.jpg)