A new international research journal has just been launched which will be focused on film, media and digital culture and is focused on Central and Eastern Europe (that is much of the Post-Soviet space). The first issue of this bi-annual journal is now online, open to access for all- academics, interested journalists as well as film buffs interested in this area of the world. Unlike some other online titles it is truly looking for an international and multi-lingual audience. The articles can be in any of the languages spoken in Central and Eastern Europe as well as English (and indeed in the first issue articles are in four different languages: German, Ukrainian, Russian and English) and the website as a whole is trilingual: in German, Russian and English. Twelve authors were engaged in writing four peer reviewed articles, five reviews and an editorial and their geographical spread is also fairly wide: Austria, Croatia, Germany, Russia, Sweden, UK and the US just as the geographical spread of the subjects involved. There is a core editorial team of four including Natascha Drubek as Editor in Chief, Irina Schulzki as Review Sections Editor and Mario Slugan who is the Managing Editor. Among its Editorial Board are names very well-known to those interested in Soviet and Post-Soviet Cinema and a mark of true quality of thought including Naum Kleiman and Oleg Aronson as well as Vladimir Padunov from Pittsburg.

This is its official launch statement by the editorial team:

Dear colleagues and friends!

The editorial team of the international research journal APPARATUS is pleased to announce its launch and the release of its first issue.

APPARATUS is a peer-reviewed online journal focused on film, media and digital cultures in Central and Eastern Europe. The main aim of the editorial team is to keep abreast with the practice of the leading international research periodicals. Our basic editorial principles are:

OPEN ACCESS the journal is freely available online ensuring maximum accessibility and international dissemination of journal content

DOUBLE BLIND PEER REVIEW all articles undergo a double blind peer review process

The novelty of the journal consists in its MULTI-LINGUAL CONTENT

articles and reviews are published in different languages,

including those used in the regions the journal focuses on,

as well as in its MULTIMEDIA FORMAT the electronic publication allows contributors to insert not only figures and links,

but also audio- and video-files directly within texts.

APPARATUS is supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) and hosted by the Free University of Berlin. Long-term storage of published materials is ensured by the German National Library.

The initiator and chief-editor of the journal is Dr. Natascha Drubek. The international Editorial Board includes leading scholars, archivists, curators and artists in the field of media research of Central and Eastern Europe. Apparatus accepts both unsolicited and solicited submissions. The journal is published twice a year either as an open call issue or a special issue.

You can find out more about the content of the site in English, German or Russian, read the first issue and submit applications on:

www.apparatusjournal.net

The journal also has a page on Facebook which one can like and on which articles for the journal as well as other articles on relevant subject matter will be posted:

https://www.facebook.com/apparatusjournal?fref=nf

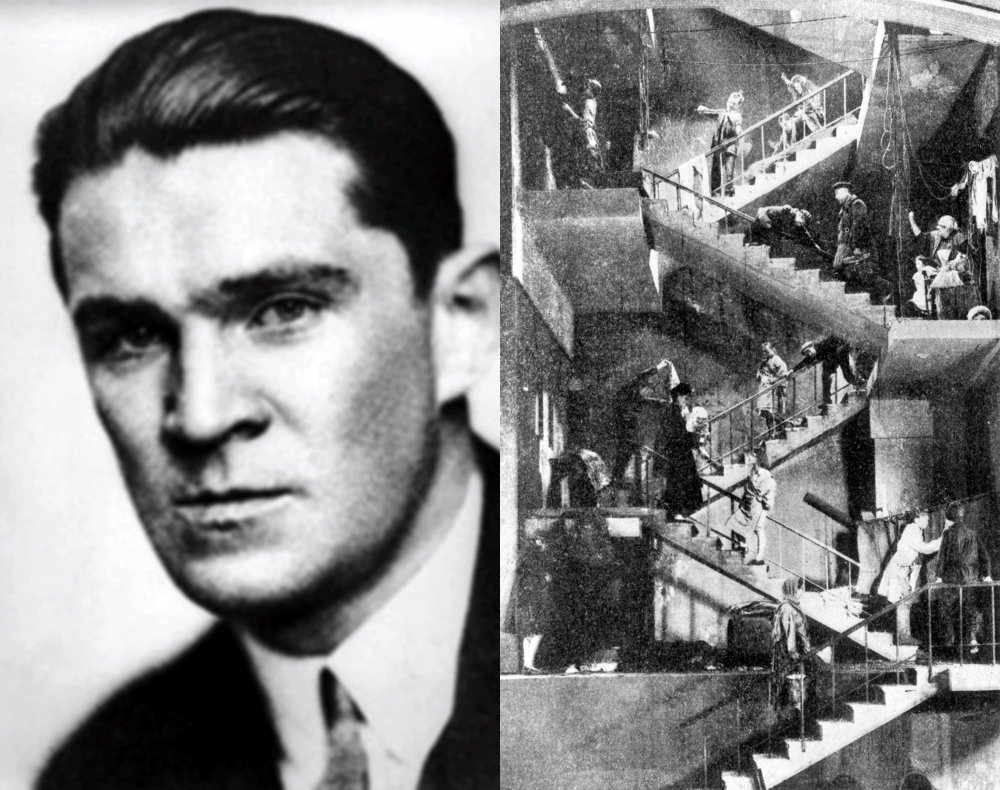

The articles published in the first issue include articles on Vertov's and Medvedkin's Film Trains and Agit Steamers of the 1920 and 30s. The next article is a much more theoretical article in Ukrainian on the difference between the use of the terms 'apparatus' and 'dispositif' (introduced by Jean-Louis Baudry in the 1970s) and how drawing a distinction between the two concepts may help us to analyse such a film like Parjanov 'The Shadow of Forgotten Ancestors' or Leonid Lukov's early post-war second part of 'A Great Life'. Other articles cover art rather than film as such with Inke Arns comparing Moscow's Collective Actions Group with Poland's Kwiekulik. Mark Lipovetsky then discusses how Pussy Riot laid bare both neo-traditionalist discourse but also the underlying hypocrisy of some of the liberal opposition. He locates the actual performances as a cultural return to and rebirth of the 'trickster trope' which was powerful in the Soviet period but declined in post-Soviet times. Then come the reviews of books (including one of Evgenii Margolit's vital 'The Living and the Dead: Notes on the History of Soviet Cinema 1920s-1960s as well as Philip Cavendish's fine book on 1920s Soviet cinematography).

A final review article is devoted to the Festival of Archive Film Belye Stolby by Georgii Borodin, the great animation specialist of the old Musei Kino team.

A great start to what promises to be a fine new venture in international research on a whole number of original topics in this growing field.