|

| A frame from Sergei Loznitsa's Austerlitz, one of the most impressive films of the Art Doc Fest |

It is quite rare to find a film festival where nearly every film watched has something to recommend about it each deserving a single blog post about them. But it is precisely in Russian or Russian-language documentary film festivals that one discovers an extraordinary variety which is not, alas, matched in contemporary Russian-language narrative cinema events. Moreover, it is often the case that some of the most interesting names that have emerged in Russian-language feature films are directors who have also worked with documentary cinema in their careers (and often these directors criss-cross between the two) : this is especially true of two of the biggest names in the post-Soviet firmament- Alexander Sokurov and Sergei Loznitsa. Also among the most interesting of upcoming directors a director like Ivan I. Tverdovsky also has had a grounding in the documentary field. With the increasingly poor selection of films at Russia's showcase festival Kinotavr (as well as the fact that documentaries are increasingly included in the dozen or so competition films shown there: this year two documentaries both already shown at least year's Art Doc Fest were included in the competition programme), it seems that the interest that there is in contemporary Russian cinema would do well to turn to the Russian or Russian-language documentary field rather than feature films in the foreseeable future.

Here are some of the picks alongside Konstantin Selin's film that I discussed in a previous blog on this festival.

|

| A scene from Anna Moiseenko's Songs of Abdul. |

1) Anna Moiseenko's Songs of Abdul is not only one of the few Russian-language documentaries on migrants or migration in recent years (with the notable exception of Denis Shabaev's Not My Job) and so deserving of interest for choosing a subject matter that, for some reason, Russian documentary filmmakers rarely choose but is also innovative in a formal way. The narrative commentary formally absent in this film as it is in most films by the razbezhkintsy (former students of Marina Razbezhkina) is, nonetheless, replaced by the songs of the documentary protagonist, Abdumamadi Gulmamad. In many ways not only has Moiseenko found a documentary protagonist who manages to illuminate many (often conflicting) worlds (not simply the world of a migrant but also that of an artist, and moreover, an artist rooted in his own world who finds himself momentarily at the centre of the Moscow art world at a Golden Mask awards ceremony) but who also becomes, in many ways, the Narrating Subject of this film as much as the director through the commentary of the songs. Indeed in many ways the input by the documentary protagonist seems also to add to the humour of this film (the scene of the Golden Mask awards being a case in point). Indeed it manages to be one of the most humorous as well as being one of the most socially innovative films on show at Art Doc Fest. By the protagonist telling his Odyssean tale as migrant through his songs and so structuring the film directed by Anna Moiseenko and shot by her and Ekena Shalkina. Moiseenko and Shalkina illustrated both his homecoming after 10 years to his wife and family in a small village in the Pamir mountains and his life in Moscow along with the endless labour and housing issues that a migrant in Moscow faces as well as the looming threat of deportation that Abdul's fellow migrants faced.

|

| The film director of Songs of Abdul, Anna Moiseenko |

2) Elena Demidova's The Last Man is a continuation of her film Lyosha on the forest fires of 2010. Demidova gives us both a superb choice of documentary hero and a highly reflexive film on the relationship between the documentarian and their documentary protagonist as well as something of a mini encyclopaedia of Russian village life. Along with the footage from the earlier film in the first part of the documentary and the extraordinary monologue of the main protagonist, in the second part it details the growing dynamic between documentarian and documentary hero ending with a phone call from Lyosha's wife demanding an end to all contact with the film's protagonist. In this way Demidova reveals the dynamics of author and subject underlying (but usually hidden from) a documentary film and in so doing brilliantly unmasks the narrative stability of a documentary portrait by foregrounding the relationship between film director and protagonist. In spite of its length (two hours) the film nevertheless finds a way of keeping the audience hooked by its portraits not just of the protagonist but also of his neighbours. There is surely enough 'cinema' to keep the audience going.

3)

|

| The film director of Six Musicians as a backdrop to a city, Tatyana Danilyants |

Tatyana Danilyants' Six Musicians as a backdrop to a city is a very different film to many of those shown at Art Doc Fest. Like many of Danilyants' films this is a city film. Not this time a film of Venice but one of Yerevan. A city film linked inextricably to its music and, in particular,to six musicians who the director felt represented a special bond to the city. Allowing them to choose the locations to be filmed, Danilyants encouraged the musicians to reveal to the viewer their city while she reveals the extraordinary vitality and versatility of the music of Yerevan. One can not help noting that Danilyants is the only documentary filmmaker in Russia making a 'city film' of any kind and this makes her films strangely unique and, in the context of Russian documentary, extremely innovative. Of course her films are not centred on Russian cities but of very particular cities on the periphery of the Slavic world but, all the same, this foregrounding of cities, this relating documentary heroes to their location and transforming the city into the ultimate protagonist of the film makes for a cinema that is almost untimely and radically opposed to much of Russian-language documentary. Indeed after watching a documentary by Danilyants one starts to wonder why the city as subject is so absent in other Russian-language films. In terms of the film itself the use of archive footage of the tragic late 80s and early 90s of Yerevan as well as one of the musicians (Lilit Pipoyan, the only female musician in the film and, for me, one of the most memorable protagonists) choice of a peripheral location of the city added authenticity to the film.

|

| A still from Tatyana Danilyants' film Six musicians as a backdrop to a city |

4)

|

| The film director of Naked Life, Daria Khrenova |

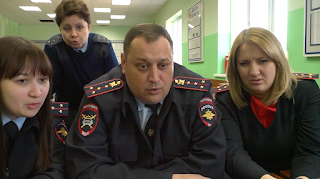

|

| A still from Daria Khrenova's Naked Life in which police officers watch Pavlensky's art actions on a screen |

There are a whole host of other films deserving of accounts. And there are films which will surely receive (and have already achieved) much international coverage. To be brief about Sergei Loznitsa's Austerlitz is a rather impossible task and in many ways it was the film that for me most stood out during the festival. Again the film Close Relations by Mansky on Ukraine also deserves a rather lengthy piece. Thankfully Carmen Gray in an article mentioned earlier has written about these films at some length for Senses of Cinema. Many films deserve to be written about at a later time. Alina Rudnitskaya's Catastrophe is a film rather unlike some of her previous odysseys through the institutions but developing them into a very poignant piece on one of the worst post-Soviet catastrophic incidents at a hydro-electric station. And then there are the films which time constraints meant sacrificing and desperately hoping for another chance to watch them.

|

| A frame from Alina Rudnitskaya's film Catastrophe on a disaster at a hydro-electric power station and its aftermath |

No comments:

Post a Comment